Registered Magna Charta or Crusader Knights Templar

Fulk V, King of Jerusalem (1131-1143) 1089 – 1143 1st Crusade

William de Ferrers, 3rd Earl of Derby – 1190 3rd Crusade

Hugh V de Gournay, Lord of Gournay – 1214 3rd Crusade

William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke 1146 – 1219 Crusades of 1184-6

Gilbert de Lacy, Templar Precentor in Tripoli – 1160 Battle of Harim, 1164

Robert de Roos (Magna Charta Surety) – 1227 Unknown

Afonso I Henriques, King of Portugal 1110 – 1185

Ramon III de Berenguer 1082 – 1131

Eudes I de Grancey 1110 – 1181

Hugh I de Troyes, Count of Champagne 1093 – 1126

Robert IV of Sablé, Grand Master 1191-1192 – 1193 3rd Crusade

Hugh V, Viscount of Châteaudun – 1140 Holy Land visit

Humbert III de Beaujeu 1120 – 1174

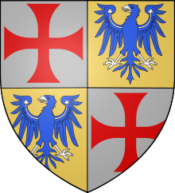

Fulk V, Count of Anjou, King of Jerusalem

Fulk V (1092–1143), called “le Jeune” (the younger), was a French nobleman who was the Count of Anjou 1109 to 1129, Count of Maine (jure uxoris) 1110–1129, a crusader, Knight Templar and the King of Jerusalem (jure uxoris) from 1131 to his death. [1]

Fulk went on crusade in 1119 or 1120 and became attached to the Knights Templar (Orderic Vitalis). When he returned to Anjou, Fulk left 100 knights behind for a year to help defend the Kingdom. He returned, late in 1121, after which he began to subsidize the Templars, maintaining two knights in the Holy Land for a year. (He continued to pay the Templars a substantial yearly donation for the rest of his life.)

By 1127 Fulk was preparing to again return to Anjou when he received an embassy from King Baldwin II of Jerusalem. Baldwin II had no male heirs but had already designated his daughter Melisende to succeed him. Baldwin II wanted to safeguard his daughter’s inheritance by marrying her to a powerful lord. Fulk was a wealthy crusader, experienced military commander and a widower. His experience in the field would prove invaluable in a frontier state always in the grip of war.

However, Fulk held out for better terms than mere consort of the Queen; he wanted to be king alongside Melisende. Baldwin II, reflecting on Fulk’s fortune and military exploits, acquiesced. Fulk abdicated his county seat of Anjou to his son Geoffrey and left for Jerusalem, where he married Melisende on 2 June 1129. Later Baldwin II bolstered Melisende’s position in the kingdom by making her sole guardian of her son by Fulk, Baldwin III, born in 1130.

Fulk and Melisende became joint rulers of Jerusalem in 1131 with Baldwin II’s death. From the start Fulk assumed sole control of the government, excluding Melisende altogether. He favored fellow countrymen from Anjou to the native nobility. The other crusader states to the north feared that Fulk would attempt to impose the suzerainty of Jerusalem over them, as Baldwin II had done; but as Fulk was far less powerful than his deceased father-in-law, the northern states rejected his authority. Melisende’s sister Alice of Antioch, exiled from the Principality by Baldwin II, took control of Antioch once more after the death of her father. She allied with Pons of Tripoli and Joscelin II of Edessa to prevent Fulk from marching north in 1132; Fulk and Pons fought a brief battle and Alice was exiled again.

In Jerusalem as well, Fulk was resented by the second generation of Jerusalem Christians who had grown up there since the First Crusade. These “natives” focused on Melisende’s cousin, the popular Hugh II of Le Puiset, count of Jaffa, who was devotedly loyal to the Queen. Fulk saw Hugh as a rival, and it did not help matters when Hugh’s own stepson accused him of disloyalty. In 1134, in order to expose Hugh, Fulk accused him of infidelity with Melisende. Hugh rebelled in protest. Hugh secured himself to Jaffa, and allied himself with the Muslims of Ascalon. He was able to defeat the army set against him by Fulk, but this situation could not hold. The Patriarch interceded in the conflict, perhaps at the behest of Melisende. Fulk agreed to peace and Hugh was exiled from the kingdom for three years, a lenient sentence.

However, an assassination attempt was made against Hugh. Fulk, or his supporters, were commonly believed responsible, though direct proof never surfaced. The scandal was all that was needed for the queen’s party to take over the government in what amounted to a palace coup. Author and historian Bernard Hamilton [pl] wrote that Fulk’s supporters “went in terror of their lives” in the palace. Contemporary author and historian William of Tyre wrote of Fulk “he never attempted to take the initiative, even in trivial matters, without (Melisende’s) consent”. The result was that Melisende held direct and unquestioned control over the government from 1136 onwards. Sometime before 1136 Fulk reconciled with his wife, and a second son, Amalric was born.

Sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fulk,_King_of_Jerusalem

[1] Ordericus Vitalis, The Ecclesiastical History of England and Normandy, trans. Thomas Forester, Vol. 4 (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1856), p. 44.

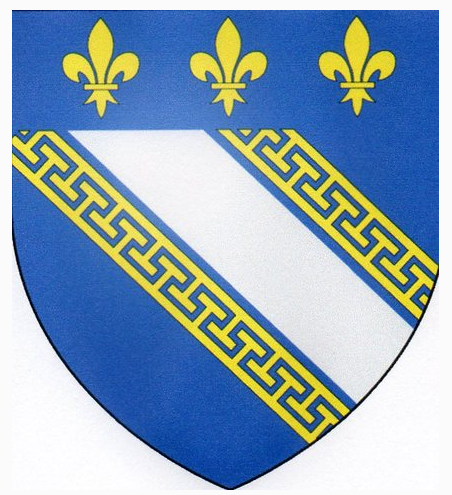

William de Ferrers, 3rd Earl of Derby

William I de Ferrers, 3rd Earl of Derby (died 1190) was a 12th-century English Earl who resided in Tutbury Castle in Staffordshire and was head of afamily which controlled a large part of Derbyshire known as Duffield Frith. He was also a Knight Templar.

William was the son of Robert de Ferrers, 2nd Earl of Derby, and his wife, Margaret Peverel. He succeeded his father as Earl of Derby in 1162. He was married to Sybil, the daughter of William de Braose, 3rd Lord of Bramber, and Bertha of Hereford.

William de Ferrers was one of the Earls who joined the rebellion against King Henry II of England led by Henry’s eldest son, Henry the Younger, in the Revolt of 1173–1174, sacking the town of Nottingham. Robert de Ferrers II, his father, had supported Stephen of England and, although Henry II had accepted him at court, he had denied the title of earl of Derby to him and his son.[1] In addition, William had a grudge against Henry because he believed he should have inherited the lands of Peveril Castle through his mother. These, King Henry had previously confiscated in 1155 when William Peverel fell into disfavor.

With the failure of the revolt, de Ferrers was taken prisoner by King Henry, at Northampton on the 31 July 1174, along with the King of Scots and the earls of Chester and Lincoln, plus several his Derbyshire underlings and was held at Caen. He was deprived of his castles at Tutbury and Duffield and both were put out of commission (and possibly Pilsbury.) In addition to defray the costs of the war Henry levied a so-called “Forest Fine” of 200 marks.

He seems to have afterwards regained the confidence of Henry II and showed his fidelity to the next Sovereign, King Richard I, by accompanying him in his expedition to the Holy Land, joined the Third Crusade and died at the Siege of Acre in 1190.[2]

William de Ferrars Preceptory No.530 is a Knight Templar preceptory named after William de Ferrars. This preceptory is stationed in Burton upon Trent.

He was succeeded by his son William de Ferrers, 4th Earl of Derby.

Sources: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_de_Ferrers,_3rd_Earl_of_Derby

Warren, W.L. 1973. Henry II. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 0-413-25580-8

[1] Turbutt, G., (1999) A History of Derbyshire. Volume 2: Medieval Derbyshire, Cardiff: Merton Priory Press

[2] Bland, W., 1887 Duffield Castle: A lecture at the Temperance Hall, Wirksworth Derbyshire Advertiser

Hugh V de Gournay, Lord of Gournay

Hugh V de Gournay, Died: 25 Oct 1214, Rouen was the son of Hugh IV de Gourney and his second wife Melisende de Coucy, widow of Adeleme Châtelain d´Amiens, daughter of Thomas de Marle Comte d´Amiens, Seigneur de Coucy, de Marle et de Boves & his third wife Mélisende de Crècy.

Hughes V founded Clairruissel priory, by undated charter.

Ralph de Diceto records that “Hugo de Gornai, tam pater quam filius” were captured in 1173 during the rebellion of Henry the Young King against his father Henry II King of England.

In 1190 he was granted the manor of Houghton Regis, co. Bedford. In 1191 he accompanied King Richard on the 3rd Crusade. At the capture of Acre, he commanded 100 knights.

In 1193, he swung over temporarily to King Philip’s side and his manors of Houghton and Bledlow were taken. In 1202 the manor of Wendover was re-granted to him. In 1202 he joined the French side and Wendover was granted to Ralph de Tilley. In 1206 he was pardoned at the instance of Otho the Emperor and permitted to return to England.

He was sheriff of cos. Buckingham and Bedford in 1214, being then weighed down with sickness.

Hugh de Gournay died 25 October 1214 at Rouen in Normandy after donning the garb of a Templar and discarding it by apostasy.[1]

He married before 1193 Juliane de Dammartin, daughter of Aubri II de Dammartin, Count of Dammartin, seigneur of Lillebonne-en-Normandie, by Mahaut (or Mabile), daughter of Renaud II, Count of Clermont-en-Beauvaisis.

“Hugo de Gornaco” donated property to Fécamp, for the souls of “Juliane uxoris mee et puerorum meorum”, by charter dated 1202.

They had two sons, Gerard and Hugh, and one daughter, Millicent.

Sources.

[1] Daniel Gurney, Record of the House of Gournay (1848), pp. 22 (chart), 128-183. Bedfordshire Historical Record Society 7 (1922): 153-157; 19 (1937): charts fol. pg. 99. Oxfordshire Record Society 7 (1925): 7-15. J. G. Jenkins, Cartulary of Missenden Abbey 1 (1938): 164-165, 188, 208-209, 244-245; 3 (1962): 13-16. Paget (1957), 266: 1-4 (sub Gurnay).]

http://knight-france.com/geneal/names/2768.htm

http://cybergata.com/roots/3187.htm

William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke

William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke (1146 or 1147 – 14 May 1219), also called William the Marshal, was an Anglo-Norman soldier and statesman. He served five English kings –Henry II, his sons the “Young King” Henry, Richard I, and John, and John’s son Henry III.

Knighted in 1166, he spent his younger years as a knight errant and a successful tournament competitor; Stephen Langton eulogized him as the “best knight that ever lived.” In 1189, he became the de facto Earl of Pembroke through his marriage to Isabel de Clare, though the title of earl would not be officially granted until 1199 during the second creation of the Pembroke Earldom. In 1216, he was appointed protector for the nine-year-old Henry III, and regent of the kingdom.

Before him, his father’s family held a hereditary title of Marshal to the king, which by his father’s time had become recognized as a chief or master Marshalcy, involving management over other Marshals and functionaries. William became known as ‘the Marshal’, although by his time much of the function was delegated to more specialized representatives. Because he was an Earl, and known as the Marshal, the term “Earl Marshal” was commonly used and later became an established hereditary title in the English Peerage.

In 1170, Marshal was appointed as Young King Henry’s tutor-in-arms by the Young King’s father, Henry II. Young King Henry declared war against his brother, Richard the Lionheart, in January 1183, with Henry II siding with Richard. However, the Young King became sick in late May, and died on 11 June 1183. On his deathbed, the Young King asked Marshal to fulfill the vow the Young King had made in 1182 to take up the cross and undertake a crusade to the Holy Land, and after receiving Henry II’s blessing Marshal left for Jerusalem in late 1183.Nothing is known of his activities during the two years he was gone, except that he fulfilled the Young King’s vow, and secretly committed to joining the Knights Templar on his deathbed.

During the reign of King John, William remained loyal to the crown throughout the hostilities between John and his barons, which culminated on 15 June 1215 at Runnymede with the sealing of Magna Carta. On 11 November 1216 at Gloucester, upon the death of King John, William Marshal was named by the king’s council (the chief barons who had remained loyal to King John in the First Barons’ War) to serve as protector of the nine-year-old King Henry III, and regent of the kingdom. Despite his advanced age (around 70) he prosecuted the war against Prince Louis and the rebel barons with remarkable energy. In the battle of Lincoln, he charged and fought at the head of the young King’s army, leading them to victory. He was preparing to besiege Louis in London when the war was terminated by the naval victory of Hubert de Burgh in the straits of Dover.

Marshal’s health finally failed him early in 1219. In March 1219 he realized that he was dying, so he summoned his eldest son, also William, and his household knights, and left the Tower of London for his estate at Caversham in Berkshire, near Reading, where he called a meeting of the barons, Henry III, the Papal legate Pandulf Verraccio, the royal justiciar (Hubert de Burgh), and Peter des Roches (Bishop of Winchester and the young King’s guardian). William rejected the Bishop’s claim to the regency and entrusted the regency to the care of the papal legate; he apparently did not trust the Bishop or any of the other magnates that he had gathered to this meeting. Fulfilling the vow he had made while on crusade, he was invested into the order of the Knights Templar on his deathbed. He died on 14 May 1219 at Caversham, and was buried in the Temple Church in London, where his tomb can still be seen.

Sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Marshal,_1st_Earl_of_Pembroke

Kingsford, Charles Lethbridge (1885–1900). “Marshal, William (d.1219)”. Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). “Pembroke, Earls of”. Encyclopedia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 78–80.

Gilbert de Lacy, Precentor of the Knights Templar in Tripoli

Gilbert de Lacy (died after 1163) was a medieval Anglo-Norman baron in England who spent much of his life trying to recover his father’s English lands, and eventually succeeded. Around 1158, de Lacy became a Templar and went to the Holy Land, where he was one of the commanders against Nur ad-Din in the early 1160s. He died after 1163.

Gilbert de Lacy was the son of Roger de Lacy, who in turn was the son of Walter de Lacy who died in 1085. Roger de Lacy was banished from England in 1096, and his estates were confiscated. These lands, which included substantial holdings along the border with Wales, were given to Pain fitzJohn, Josce de Dinan and Miles of Gloucester. Roger de Lacy’s lands in Normandy, however, were not confiscated, as they were held of the Bishop of Bayeux in feudal tenure.

Gilbert de Lacy had inherited his father’s lands in Normandy by 1133, and by 1136 was in England with King Stephen of England. Although de Lacy recovered some of his father’s lands, the border lands near Wales were not recovered. Among the lands Gilbert recovered were lands about Weobley. He also was granted some lands in Yorkshire that had been in dispute.

Although de Lacy had spent time at Stephen’s court, during the civil war that occurred during Stephen’s reign, he switched sides and served Stephen’s rival, Matilda the Empress. In 1138, he was besieged by the king at Weobley along with his cousin Geoffrey Talbot, but both men escaped when the king took the castle in June. De Lacy also led an army in an attack against Bath in the service of the Empress, along with Geoffrey Talbot, which also occurred in 1138 and which some historians have seen as the opening act of the civil war.

De Lacy witnessed charters of the Empress in 1141. During the latter 1140s, de Lacy was able to recover many of his father’s Welsh marcher lands, and one of his efforts at Ludlow was later embroidered in the medieval romance Fouke le Fitz Waryn. He and Miles of Gloucester were claimants to many of the same lands, and during Stephen’s reign were generally on opposite sides of the succession dispute. In June 1153, de Lacy was in the company of Matilda’s son, Henry fitzEmpress, who became King Henry II of England in 1154.

De Lacy gave land to the cathedral chapter of Hereford Cathedral. He also gave a manor at Guiting to the Knights Templar and two churches, at Weobley and Clodock to Llanthony Priory, which was a monastery founded by his family.

Around 1158 de Lacy surrendered his lands to his eldest son Robert when the elder de Lacy became a member of the Knights Templar. He then travelled through France to Jerusalem, where de Lacy became precentor of the Templars in the County of Tripoli. In 1163, de Lacy was one of the crusader army commanders fighting against Nur ad-Din.

De Lacy’s year of death is unknown, but he was commemorated on 20 November at Hereford Cathedral. Robert died without children sometime before 1162, when Gilbert’s younger son Hugh de Lacy inherited the lands.

The Gesta Stephani called de Lacy “a man of judgement and shrewd and painstaking in every operation of war”.

Sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gilbert_de_Lacy

Lewis “Lacy, Gilbert de” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Keats-Rohan, K. S. B. Domesday Descendants: A Prosopography of Persons Occurring in English Documents, 1066–1166: Pipe Rolls to Cartae Baronum., (Ipswich, UK: Boydell Press., 1999). pp. 536-538

Robert de Roos

Sir Robert de Ros (died about 1227) was an Anglo-Norman feudal baron, soldier, and administrator, who was one of the Twenty-Five Barons appointed under clause 61 of the 1215 Magna Carta agreement to monitor its observance by King John of England.[1][2]Born about 1182, he was the son and heir of Everard de Ros (died before 1184) and his wife Roese (died 1194), daughter of William Trussebut, of Warter.[1][2]

Left fatherless, his lands were initially in the keeping of the Chief Justiciar of England, Ranulf de Glanvill.[2] In 1191, though under age, he paid a 1000 mark fee to inherit his father’s lands.[1] In that year he also married a widow who was an illegitimate daughter of King William I of Scotland.[1][2] Later he inherited from his mother one-third of the Trussebut estates, which included lands near the town of Bonneville-sur-Touques in Normandy, of which he became hereditary bailiff and castellan.[1][2]

Like many magnates, he had an uneasy relationship with King John after 1199. He witnessed the King’s charters, served in his armies, went on diplomatic missions for him (one in 1199 to Ros’ father-in-law in Scotland), and on one occasion was reported gambling with him in Ireland. Tension arose in 1205, when John ordered his lands to be seized but later relented.[1] It was possibly then that his younger son was taken as a hostage by the King.[1][2]

In 1206 he was given permission to mortgage his lands if during the next three years he went to Jerusalem, as a crusading knight or as an individual pilgrim.[1][2] In 1209, he was sent again on a diplomatic mission to Scotland but does not seem to have gone to Palestine,[1] for in 1210 he was serving with John in Ireland.[2]

In October 1213 he was one of the witnesses when John surrendered England to the authority of the Pope and he was one of the twelve guarantors appointed to ensure John kept his promises.[1][2] Throughout the disturbances of 1214 and the first quarter of 1215 he remained loyal to John, being rewarded with royal manors in Cumberland and royal support for the election of his aunt as abbess of Barking Abbey. However, he then joined the rebel barons as one of the 25 chosen to enforce observance of the Magna Carta agreement, being appointed by them to control Yorkshire and possibly Northumberland. For this he was excommunicated by the Pope, and John gave his lands to William de Forz.[1]

In 1225 he was one of the witnesses to the reissue of Magna Carta and by the end of 1226 had entered a monastic order,[1][2] possibly the Knights Templar. His Helmsley estates, where he had fortified the castle, then went to his elder son, while Wark, also fortified by him, went to the younger.[2][3] He died that year, or in 1227, and was buried in the Temple Church in London.[1]

He was a supporter of the Knights Templar, giving them lands in Yorkshire that included Ribston, where they set up a commandery. At Bolton in Northumberland, he founded a leper hospital dedicated to St Thomas Becket,[1] endowing it with extensive lands. He was also a benefactor of Rievaulx Abbey, Newminster Abbey, and Kirkham Priory.[2]

Sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_de_Ros_(died_1227)

[1] Thomas, Hugh M. (22 September 2005), “Ros, Robert de (c. 1182–1226/7)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Subscription or UK public library membership needed), retrieved 7 May 2018

[2] Geoffrey H. White, ed. (1949), “Ros”, The Complete Peerage, XI, London: The St Catherine Press, p. 92, retrieved 7 May 2018

[3] Vincent, Nicholas (25 May 2006), “Ros, Robert de (d. c. 1270)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Subscription or UK public library membership needed), retrieved 7 May 2018

Afonso I, King of Portugal

Afonso I, also called Afonso Henriques, by name Afonso the Conqueror, Portuguese Afonso o Conquistador, (born 1109/11, Guimarães, Port.—died Dec. 6, 1185, Coimbra), the first king of Portugal (1139–85), who conquered Santarém and Lisbon from the Muslims (1147) and secured Portuguese independence from Leon (1139).

Alfonso VI, emperor of Leon, had granted the county of Portugal to Afonso’s father, Henry of Burgundy, who successfully defended it against the Muslims (1095–1112). Henry married Alfonso VI’s illegitimate daughter, Teresa, who governed Portugal from the time of her husband’s death (1112) until her son Afonso came of age. She refused to cede her power to Afonso, but his party prevailed in the Battle of São Mamede, near Guimarães (1128). Though at first obliged as a vassal to submit to his cousin Alfonso VII of Leon, Afonso assumed the title of king in 1139.

By victory in the Battle of Ourique (1139) he was able to impose tribute on his Muslim neighbors; and in 1147 he further captured Santarém and, availing himself of the services of passing crusaders, successfully laid siege to Lisbon. He carried his frontiers beyond the Tagus River, annexing Beja in 1162 and Évora in 1165; in attacking Badajoz, he was taken prisoner but then released. He married Mafalda of Savoy and associated his son, Sancho I, with his power. By the time of his death he had created a stable and independent monarchy.

Sources: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Afonso-I-king-of-Portugal;

Weis, Frederick “Ancestral Roots of Certain American Colonists…” 112:25

Robert IV of Sablé, Grand Master

Robert IV de Sablé (1150 − 23 September 1193) was Lord of Sablé, the eleventh Grand Master of the Knights Templar from 1191 to 1192 and Lord of Cyprus from 1191 to 1192. He was known of as the Grand Master of the Knights Templars and the Grand Master of the Holy and Valiant Order of Knights Templars.

He was born to a respected military family in Anjou and was a leading Angevin vassal of the King. His lordship was based in a cluster of lands in the River Sarthe valley, which he inherited in the 1160s. He married Clemence de Mayenne (died before 1209). He was succeeded in Anjou by his daughter Marguerite de Sablé, who by marriage passed the entire estate to William des Roches, also a knight of the Third Crusade. Robert died in the Holy Land on 23 September 1193. Although there are no exact records of his birth date, it is believed that he was relatively old at the time of his death compared to the average life expectancy of the 12th century.

During the Angevin Civil War, in 1173, Sablé supported Henry the Young King, heir apparent to the throne of the Kingdom of England and duchy of Normandy, in a revolt against his father Henry II during the Revolt of 1173-1174. The uprising was crushed but Robert must have remained in favor with the Angevin Kings, as Richard would later be instrumental in his appointment as Grand Master. He contributed money to French monastic houses in 1190 as a way of making amends.

Despite only having a short tenure, Sablé’s reign was filled with successful campaigning. Before his election as Grand Master, he led King Richard I’s navy from England and Normandy to the Mediterranean, getting involved in the Reconquista in passage. The combined might of Richard the Lionheart’s strategy, seasoned troops, and the elite Templar knights scored many victories. During the Third Crusade, they laid siege to the city of Acre, which soon fell. Throughout August 1191, they also recaptured many fortresses and cities along the Levantine coast in the Eastern Mediterranean, which had been lost previously.

The new coalition’s finest hour was the Battle of Arsuf, on 7 September 1191. Saladin’s Muslim forces appeared to have become far stronger than the Christians, and a decisive victory was desperately needed. Pooling all the crusaders’ strength, the Knights Hospitaller joined the ranks, plus many knights from Sablé’s native Anjou, Maine, and Brittany. They met Saladin’s troops on the dry plains and soon broke his ranks. Those who stayed to fight were killed, and the remaining Islamic troops were forced to retreat.

At the end of 1191, Richard the Lionheart agreed to sell Cyprus to the Templars for 25,000 pieces of silver. Richard had plundered the island from the Byzantine forces of the tyrant Isaac Comnenus of Cyprus some months earlier and had no real use for it. The Hospitallers would later establish solid bases on the islands of Rhodes and Malta, but Sablé failed to do the same with the island of Cyprus. He was lord for two years, until he gave (or sold) the island to Guy de Lusignan, King of Jerusalem, as he was without a kingdom. Sablé did manage to establish a Chieftain House of the Order in Saint-Jean d’Acre, which remained for almost a century.

Sablé was lucky to have been Grand Master at all, as at the time of Gerard de Ridefort’s death, he was not even a member of the Templar Order. However, the senior knights had become increasingly opposed to Masters fighting on the front line, and the capture and beheading of Grand Master Gerard de Ridefort became the final straw. They delayed elections for over a year so that the rules regarding active service of Grand Masters could be reviewed. During this hiatus, Sablé did join the order, just in time to be considered for election. When he was made Grand Master, he had been a Templar knight for less than a year. He died in 1193.

Sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_IV_of_Sabl%C3%A9

Hugues V, Viscount of Châteaudun

Hugues IV (died 1180), Viscount of Châteaudun, son of Geoffrey III, Viscount of Châteaudun, and Helvise, Dame of Mondoubleau, daughter of Ilbert “Payen” de Mondoubleau. He became Lord of Mondoubleau upon his mother’s death, based on her inheritance, and acquired the lordship of Saint-Calais by marriage.

Hugues took his first trip to the Holy Land with his father in 1140. In 1059, Hugues’ second trip to the Holy Land was accompanied by encroachments of his land by his third cousin Rotrou IV, Count of Perche. In response, Hugues captured the land of Villemans, to the detriment of the church and priory of the Holy Sepulchre of Châteaudun. Yves, Abbot of Saint-Denis Nogent-le-Rotrou, supported Rotrou is this dispute. The affair ended in 1166 through a judgement of Theobald V, Count of Blois and his brother William of the White Hands, then Bishop of Chartres.

In 1118, nine French knights led by Hugues de Payens created a religious militia which was to become the Order of the Temple. The members of the Order were monks and soldiers and obeyed the rules elaborated by a council gathered at Troyes Cathedral in France in January 1128.

The Templars settled in Arville around 1130 on an estate of 2500 acres, given for their disposal by Hugues’ father Geoffrey (referred to as Lord of Mondoubleau in local historical records). Hugues V founded the Commanderie d’Arville of the Knights Templar in 1135 on land donated earlier by his father. The Commanderie became a farming center, a recruitment center, a place of worship, and a training base for the knights waiting for their departure to the Holy Land. The Templars lived here until their arrest, accused of heresy by Philip IV of France in 1307. The Commanderie remains a unique monument and one of the best preserved Commanderie in France.

At the request of Theobald V, he imprisoned Sulpice II d’Amboise and his sons in a dungeon of the castle of Chateaudun in order to force him to transfer his Chateau de Chaumont to Theobald’s control. Sulpice was killed in 1153 after being tortured, but with his chateau’s ownership intact. His sons were released upon intervention by their cousin Henry Plantagenet, future King of England.

In 1154, Hugues married Marguerite de Saint-Calais, daughter of Sylvestre de Saint-Calais, and heiress to the lordship of Saint-Calais.

Given the ties of Hugues’ family with the Knights Templar, the common use of the name Payen, and the relationships with the House of Montdidier, it is possible that Payen de Montdidier, one of the founding Templar nine knights, is related to the family.

Sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hugh_V,_Viscount_of_Ch%C3%A2teaudun

Settipani, Christian, Les vicomtes de Châteaudun et leurs alliés, dans Onomastique et Parenté dans l’Occident médiéval, Oxford, Linacre, Unit for Prosopographical Research, 2000

Europäische Stammtafeln, Vol. III, Les Vicomtes de Châteaudun

Histoire du Perche, Par Philippe Siguret, Michel Fleury, Publié par Fédération des amis du Perche, 2000

Eudes I de Grancey 1110-1181

Hugh I de Troyes, Count of Champagne 1093-1126

Hugh, Count of Champagne One of the earliest members of the Templars was also one of the few members of the high nobility to join. Hugh of Champagne remains one of the more mysterious of the first Templars.

As with so much of the politics in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, the story of Hugh, first count of Champagne, is that of family. When he was born, the county of Champagne didn’t exist. For most of his life he called himself the count of Troyes, which was the main holding of his ancestors.

Hugh was the youngest son of Thibaud I, who was count of Blois, Meaux, and Troyes, and of Adele of Bar-sur-Aube. Thibaud had gained some of his property by taking over lands belonging to a nephew.1 Therefore, he had something to give to Hugh, his last-born son. Hugh’s older brother, Stephen-Henry, got the best property, that of Blois and Meaux. Hugh inherited Troyes and other bits from his mother and the property of his middle brother, Odo, who died young.2

Hugh did not go on the First Crusade in 1096, although Stephen-Henry did. He may not have been interested or he may have been too busy subduing all his far-flung properties. One of these properties was the town of Payns not far from Troyes. A son of the lord of the town, Hugh de Payns, became one of Hugh’s supporters and a member of his court.3

Hugh scored a coup in 1094 by his marriage to Constance, daughter of Philip I, king of France. She brought with her the dowry of Attigny, just north of Hugh’s lands.

As the twelfth century dawned, Hugh seemed to be an up-and-coming young nobleman, with an expanding amount of land and royal connections.

In 1102, Stephen-Henry died in battle in Palestine. He left several young sons and a formidable wife, Adele, the daughter of King Henry I of England. This was Stephen’s second trip to the Holy Land. It was said that Adele wasn’t pleased with her husband’s military exploits on the first trip. He had deserted the crusader army before reaching Antioch. Adele insisted he return and fight more bravely before showing his face at home again.4 Stephen-Henry’s death in battle apparently satisfied her.

At about the same time, 1103, Hugh had a very strange encounter. One day while he was traveling in the valley of Suippe, a man named Alexander, a pilgrim from the Holy Land, came to see him. A charter from the convent of Avenay tells what happened next. “Hugh . . . used to ransom captives and aid the destitute. Among these was a certain Alexander, an impoverished man from overseas whom the count took into his own household. The most noble count and his family treated this man so well that he even ate and often slept in the count’s personal quarters.”5

Hugh’s confidence in Alexander was misplaced for, one night, “judging the time and place appropriate, [he] tried to slit the throat of the sleeping count.”6

The records don’t give a reason for the attack, nor do they say anything more about the pilgrim. This is one of the frustrations of historical records.

Hugh only survived the attack because his men took him directly to the nearby convent of Avenay, where he spent several months recovering. In return he gave a large donation to the nuns, whose care and prayers he felt had saved his life when doctors couldn’t.

It may have been the combination of his brother’s death and his own near miss that convinced Hugh to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. He left in 1104 and returned around 1107.7 It’s not clear whether he and his retinue aided in the ongoing fight to keep the land won by the first crusaders or simply visited the pilgrim sites.

While Hugh was off on his journey his wife, Constance, decided she’d had enough. She and Hugh had been married eleven years and had no children. Fortunately, most of the nobility of France were related in one way or another and so she was able to have the marriage dissolved on the grounds that they were cousins. This was the medieval way around the prohibition of divorce, and it was used all the time. Constance later married Bohemond I, ruler of Antioch, and ended her days there.8 Her descendants, especially the women, played important roles in the history of the Latin kingdoms.

So upon his return to Champagne in 1107, Hugh found himself single. He soon married again, this time to Elizabeth of Varais, daughter of Stephen the Hardy of Burgundy. Elizabeth was related to a number of strong, powerful women of the time. She was the niece of Clemence, countess of Flanders, and also Matilda, duchess of Burgundy. Her first cousin was Adelaide, the wife of Louis VI, king of France.

In October 1115, Count Hugh was attending Pope Calixtus II at the Council of Reims, where he and his men provided an escort to the bishop of Mainz.9 The pope was, by the way, Elizabeth’s uncle. Life was going well again for the count of Champagne.

Therefore, it was strange that when Elizabeth presented Hugh with a son, he refused to believe it was his and said so publicly. The dating of the blessed event is uncertain, around 1117. Hugh had gone on his second pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1116 and it could have been that his wife tried to convince him that she had had a fourteen-month pregnancy. But the reason Hugh gave was that his doctors had all told him that he was sterile, so he may have thought that it was chronologically possible for him to be the father.10 In any event, the child, Eudes, and his mother were repudiated.

Apparently, there was enough doubt among others of the family as to the legitimacy of the baby that no great storm of protest hit Hugh. While Eudes had friends who took his side over the years, he was never able to attract enough support to be a threat to the next count of Champagne, Hugh’s nephew, Thibaud. Eudes was given a small fief and allowed to live out his life in peace.

Hugh did not try another marriage. In 1125 he abdicated as count and returned to Jerusalem, where he joined the newly formed Templars. 11 He died there sometime after 1130.

The story of Hugh, count of Troyes and Champagne, is one of the real mysteries of the Templar saga. According to legend, the order was formed in 1119, after Hugh de Payns decided to remain in Jerusalem while Count Hugh returned to Troyes. Did the count have any influence on the decision of the future founder of the order to stay behind? As Hugh’s overlord, Count Hugh would have had to give his permission for Hugh to leave his service. Was the count part of this initial decision to form a monastic military order?

We don’t know. None of the chroniclers mention him, except to note that he ended his life as a Templar. Is it because they were embarrassed to say that the count of Champagne chose to become subservient to a man who had once been one of his vassals? Count Hugh seems to have been a consummate warrior. He spent most of his life fighting or on pilgrimage. He seems a much more likely candidate for being the founder of the Templars than Hugh de Payns.

But he wasn’t. He died as a member of the order, nothing more. Champagne went to Thibaud, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror and the son of Count Stephen-Henry, who had died as a soldier of God. And Hugh faded into a footnote to Templar history.